By Barry Kent MacKay (September 9, 2022)

As a part-time professional bird illustrator, I visit a lot of zoos to look at, and sketch, birds. But as a naturalist, a bird-lover, and part time professional animal protectionist, as well as an artist, I spend a lot more time observing birds where they belong, in their wild, natural homes. And finally, I do all of that as the son of a woman, the late Phyllis E. MacKay, who was very much a pioneer in rehabilitating wild birds, both those injured and those orphaned, so that my life has always been filled with birds, tame and wild, in and out of my home, and throughout my life.

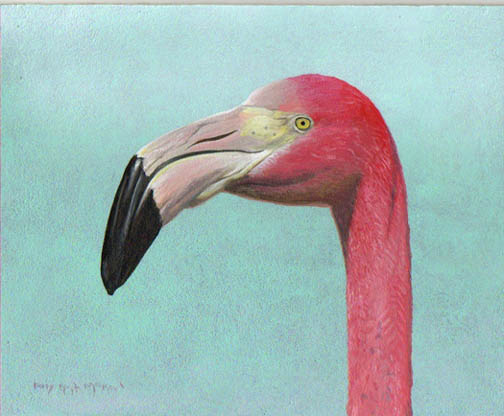

Therefore I believe that I look at birds in zoos differently than the average zoo visitor. As a matter of fact, as I stand beside cages, sketching quietly, or taking photographs, or writing down my observations, I also take note of those zoo visitors. They see almost nothing, and learn almost nothing. They will observe a parrot or a penguin, an owl or an eagle, usually sitting as if resigned to inertia, displaying only the general appearance of the bird in repose. They might enjoy the bright feathers of a flamingo or laugh at the over-sized beak of a toucan, but in balance that’s about the extent of their involvement with the birds held captive. They rarely glance at any signs that might tell them the actual name of the bird, let alone anything about the bird. And as independent studies have demonstrated, they spend only a very brief time, on average, at any one exhibit.

And when I turn my attention to the actual birds, I see little to remind me of what I have seen of the same birds in the forests, jungles, deserts, beaches, prairies and other habitats that I have had the privilege to roam, in search of birds not sitting on a fake rock or wooden perch or dabbling about in a small, concrete-lined basin, but wild and free, active and involved in the richly intricate and infinitely variable natural world. If we are to deprive birds of that freedom, that involvement, that sheer richness that is inherent to their natural lives, surely there must be a good reason.

Zoos claim they educate. But how can they educate when they not only fail to represent the way the bird actually is, but misrepresent the bird in so many ways. Name any of the most commonly seen species in zoos: Mute Swans, Greater Flamingos, Golden Pheasants, Laughing Kookaburra, Mandarin Duck, Bald Eagle…any of dozens of others…and what do you know of them as a result of seeing individuals in zoos? Where do they live; what foods do they consume; how do they fly; what is the colour, size, shape or number of their eggs; how many are there in the wild and are their numbers increasing or in decline; do they have a breeding display; what are their vocalizations; how much do they weigh; are they migratory; what predators prey upon them; what are their closest relatives…the list goes on…and at most, the very most, those very few visitors who take the time to read signs may get just a hint of what the birds actually are, a sense of the wonder that birds can evoke, a bit of knowledge about how the bird lives, when living naturally in its native home.

Often I have stood beside an aviary filled with wonderful little birds of lesser known species, an Emerald Toucanet, some species of laughing-thrush or maybe a drongo, a Paradise Tanager or a Blue-crowned Motmot or perhaps a pair of Silver-eared Mesias or maybe a Golden-fronted Leafbird…species I know and love, and admire, and watched as families pass by, not noticing the birds at all, or if seeing them, glimpsing something in silhouette against a lightbulb, or hidden behind a food dish or sleeping quietly in a corner, and so failing to appreciate just how stunningly beautiful these creatures really are.

You will notice that I do not mention the care the birds receive. That varies but too many, indeed, most, zoos I have visited and pictures of various zoos I have seen feature a plethora of ways in which, if birds must be kept captive, they should not be treated. Inappropriate cage wire, lack of shelter, badly chosen foods, lack of protection from throngs of people, stereotypical behaviour…all those things are present, certainly as a result of lack of sufficiently promulgated and enforced regulations, but also as a result of ignorance, inertia-driven force-of-habit and various economic considerations.

Morality is subjective, but not just my own, but that of, I think, a great many people, determines that carefully thought out and enforced regulations alone will not ethically allow us to justify imprisoning birds in the first place. I am not speaking as one opposed to captivity in principle. I am not one of those people who thinks that under no circumstances should any bird or other animal be kept captive, but there must be a reason of benefit to the captive, or at the very least, to the survival of its species. And understand that I have benefited from what zoos can provide to me because of the intensity of my interest in birds, although if they are caging birds for me or the relatively few people as involved with birds as I am, please do not do so! It is not justified.

No, I think that it may be morally defensible to keep birds if certain criteria are met. For example, if in doing so you are genuinely protecting the species. But with a very, very few exceptions, the birds you see in zoos in no way contribute to the conservation of the species, and even those involved in Species Survival Plans, rarely will in any way contribute to the survival of anything more than a domesticated form of the species forever held captive. The few exceptions where captivity has possibly helped save a species, such as the Nene, perhaps, or the California Condor or Whooping Crane, all three species captive breeding has existed independently of zoos, although often in conjunction with zoos and used by them to justify the existence of 99.99 percent of zoo animals whose confinement does not save the species to which they belong.

I think that it is justified to hold a bird captive for the sake of the bird…birds that have, for example, lost the ability to survive on their own in the wild. But such birds are often disfigured, and common, and not of interest to zoos.

While I think it could be argued both ways, I believe that it may be honourably justified to imprison a bird if in doing so you really teach appreciation of the bird, the species the bird belongs to and the great and mysterious complexity of nature. But I think zoos tend to do the opposite, to simplify things down to just the bird, isolated from all that contributes to its natural existence.

I don’t have a magical answer to how we can justify keeping birds in zoos, but I do know that I do believe in the capability of humans to be compassionate and intelligent and to evolve customs and traditions and needs. And I think the obligation is to reach the next level by creating means to pay proper homage to this wondrous class of animals, not by sticking them in cages and aviaries, but by using our wonderful capability for inventiveness and for technological development to really bring birds into peoples’ lives, to inform and teach and imbue that sense of wonder about birds that has governed me and my life.

We can, and should, do better.